In a recent article in National Review, Ian Tuttle tells us that “standup comedy is colliding with progressivism.” He notes that comedians like Jerry Seinfeld and Gilbert Gottfried have complained of a new political correctness they perceive in college audiences and in comedy clubs, and he cites feminists and others who routinely protest against allegedly “sexist,” “racist,” and/or “homophobic” jokes told by prominent comedians like Louis C. K. In Tuttle’s view, the “pious aspirations” of left-wing “moral busybodies” have led them to “[object] to humor that does not bolster their ideology” and “to conflate what is funny with what is acceptable to laugh at.”

No doubt he’s right about that. But what does Tuttle think is the correct attitude to take to humor? Comedy, he says, is about “speaking truth to power,” and “the comedian[‘s]… jokes are never without a bit of truth.” Indeed, he writes:

“Only the truth is funny,” comedian Rick Reynolds observed in the 1990s. The comedian, in his role as fool, can never stray beyond what is true, or he will have trouble making it funny.

In his May 2014 GQfeature about Louis C.K., Andrew Corsello identified a willingness to tell the truth about what people do and think as part of C.K.’s brilliance: “He’s always striking through the mask, Louis C.K. It’s not just a matter of braying aloud what the rest of us only dare to think; he says things we aren’t even aware we’re thinking until we hear them from C.K. That’s his genius.”

End quote. Tuttle is, of course, hardly the first to assert that comedy is essentially about telling uncomfortable truths. That Lenny Bruce, George Carlin, et al. were all in the business of “speaking truth to power” has become a cliché. But (with no disrespect to Tuttle intended) it’s also a pious falsehood. Indeed, it is exactly the samepious falsehood Tuttle rightly condemns when he sees it in progressives.

After all, the humorless progressives Tuttle criticizes don’t think the jokes they condemn really do contain any uncomfortable truths. Rather, they think these jokes promote what the critics sincerely take to be falsehoods. They think that the jokes in question do not“speak truth to power,” but rather aid and abet the powerful by facilitating lies about those who are less powerful. This is all overheated and humorless, of course, but that is what they think. In other words, they are applying Tuttle’s own criterion for evaluating humor. And if Tuttle were to respond: “OK, but these left-wingers are just wrong about where the truth lies,” then he would be guilty of taking exactly the same ideological approach humor that the left-wingers do. For of course, they would say that he is the one who is wrong about where the truth lies.

The problem is not that the progressives in question look at humor through the wrong political lens. The problem is that looking at humor through anypolitical lens, including the right one, is simply to misunderstand the nature of humor. The fact is that there does not seem to be any essential connection at all between something’s being funny and it’s conveying some truth, uncomfortable or otherwise. The uncomfortable truth is rather that lots of things really are funny even though they rest on falsehoods, and lots of things are unfunny even though they are uncomfortable truths.

It’s hardly difficult to come up with examples. To learn you have terminal cancer is to learn an uncomfortable truth. But it isn’t funny, even if you are one of the “powerful” to whom this truth is being “spoken.” Probably even your enemies won’t find it at all funny, but will feel sorry for you. And even if they are very hard-hearted and don’t feel sorry for you, it probably won’t be because they think it’s funny, but rather because they think you somehow deserve it.

Perhaps someone who thinks that there is an important link between truth and humor would respond that there are at least imaginable contexts in which this sort of truth would be funny. And that is correct -- there is such a thing as dark comedy, after all, and I’ll say more about it in a moment. But in these cases it is precisely the additional context that generates the comedy, and not the uncomfortable truth itself.

Nor is it difficult to think of examples of things that are funny even though they don’t convey truths of any sort. What truth is conveyed by a slap fight between the Three Stooges? Or lines like “Don’t call me Shirley” or “Roger, Roger. What's our vector, Victor?” in the movie Airplane? Even jokes motivated by views one takes to be false or offensive can be funny. For example, even the most ardent admirer of John Foster Dulles would have to admit that “Dull, duller, Dulles” is a pretty funny insult. In his book Comic Relief, John Morreall suggests, quite rightly in my view, that the reason “Polish jokes” were popular in the U.S. in the 1970s was not because people really thought Poles were unintelligent. George Carlin was usually pretty funny even though his views about politics and religion were usually pretty sophomoric. (In my view, anyway; of course, some readers will disagree. But even those who disagree have no doubt heard somecomedian or other tell a joke that prompted them to think: “I don’t agree with the view underlying it, but I have to admit it’s still funny.”)

Philosophers have over the centuries debated various theories about what makes something funny, and the “It’s funny because it’s true” theory is not among them. Probably the most widely accepted theory -- and, I think, the most plausible one -- is the incongruity theory, according to which we find something funny when it involves some kind of anomalous juxtaposition or combination of incompatible elements. Think of Kramer’s ridiculous antics on Seinfeld -- ineptly attempting to masquerade as a doctor, shaving with butter, preparing a meal in the shower, trying to pay for a calzone with a big sack of pennies, etc. -- or Larry David’s over-the-top reactions to minor inconveniences and offenses on Curb Your Enthusiasm. Or consider the way that the punch line of a joke typically involves some sort of reversal of what one would have expected given the setup.

To be sure, the incongruity thesis needs to be qualified in various ways. There is, for example, nothing funny about a rattlesnake you find slithering up next to you after you slip into your sleeping bag while out camping, even though there is an obvious incongruity between settling down to sleep and finding a rattlesnake next to you. However, if you “detach” yourself from such a scenario -- imagine seeing this happen onscreen in a movie, or even happening to someone else -- it certainly canseem funny. Similarly, no one who seriously embarrasses himself in public -- by giving a horrible speech or telling a joke that falls flat, by having some personal foible revealed in front of a crowd, by losing control of his bowels, or whatever -- finds it funny at the time. But such scenarios are nevertheless very common in comedy movies, and even someone to whom such a misfortune occurs often laughs about it later, as do those to whom he relates the story. It is incongruity detached from any immediate danger that is funny. (Noël Carroll suggests some other ways the incongruity theory might be refined and qualified in Humour: A Very Short Introduction.)

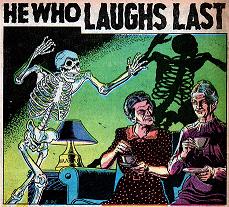

It seems to me that people often overestimate the significance of certain kinds of jokes because they fail to see that it is incongruity that is key to their effectiveness. They wrongly identify some other prominent element as key, and then overreact in either a negative or positive way. For example, some people find “dark comedy” or “black humor” offensive, because they think it reflects insensitivity to human suffering or that it is motivated by a desire to shock decent sensibilities. But that is not the case. Of course, someone who tells such a joke could be insensitive or motivated by ill-will, but the point is that he need not be. Rather, dark humor is funny precisely because of how extremethe incongruity involved typically is. (Consider, if you have the taste for this kind of humor, this example, or this one, or the work of cartoonist John Callahan.)

Similarly, the reason people find ethnic jokes or “dumb blonde” jokes funny need not be because they harbor “racist” or “sexist” attitudes. Nor need religious jokes be motivated by sacrilegious or blasphemous intent. For example, the famous Last Supper scene in Mel Brooks’ History of the World, Part Iis effective because of the extremeness of the incongruity it portrays -- the preposterous juxtaposition of Christ solemnly teaching while some annoying waiter is trying to push soup and mulled wine on the disciples. (Note that I am not addressing here the question of what sorts of jokes are appropriatefrom a moral point of view -- that’s another matter. I’m talking about why people in fact find certain things funny.)

At the other extreme, people can react in too positivea way to comedy when they fail to see that it is incongruity rather than some other prominent element that “does the work” in humor. And that is, I think, exactly what is happening when people suggest (quite absurdly, in my view) that standup comedy has some profound mission of “speaking truth to power” etc. The sober, mundane truth is rather merely that comedians like Lenny Bruce, George Carlin, or Louis C. K. say things that you are “not supposed” to say -- things that violate the rules of etiquette or decorum, or conflict with the conventional wisdom, or are odd or unusual. In other words, there is an incongruity between what they say and what people usually feel comfortable saying. Sometimes what they say captures some “uncomfortable truth,” but sometimes it’s just crackpot bloviating or rudeness. And when it is true, it isn’t the truth per se that makes it funny, but rather the incongruity.

Hence, just as critics of some forms of humor overreact because they misidentify the source and motivation of the joke (“That’s insensitive!” “That’s racist!” “That’s blasphemous!”), so too do the boosters of certain comedians ridiculously overstate the significance of what they do. “He’s a genius, a diagnostician of our social ills, an exposer of hypocrisy, he’s speaking truuuuth to powwwwer!”

Nah, he’s just some guy telling jokes. That’s all.